Can AI help us identify who the real authors of classic literature?

According to MIT, the answer is yes. In a recent, article they noted how machine learning was used to identify how much a co-author helped fill in the banks for Shakespeare's Henry VIII. They had long suspected that John Fletcher was the individual but couldn't identify what passages he wrote into the play.

Petr Plecháč at the Czech Academy of Sciences in Prague trained the algorithms using plays that Fletcher that corresponded with the time that play was written because "because an author’s literary style can change throughout his or her lifetime, it is important to ensure that all works have the same style".

Based on his analysis, it appears half the play is written by Fletcher.

The experiment is a proof-of-concept that there is a certain linguistic signature to how people author things. In a sense, it means we have a unique pattern when it comes to how we construct sentences. With respect to the experiment run by Dr. Plecháč, the algorithm was able to detect what was written Fletcher because he "often writes ye instead of you, and ’em instead of them. He also tended to add the word sir or still or next to a standard pentameter line to create an extra sixth syllable."

Can this be used within an audit?

A paper co-authored by Dr. Kevin Moffitt of Rutgers University entitled "Identification of Fraudulent Financial Statements Using Linguistic Credibility Analysis" found just that. In the paper, they explained how they used a "decision support system called Agent99 Analyzer" to "test for linguistic differences between fraudulent and non-fraudulent MD&As". The decision support system was configured to identify linguistic cues that are used by "deceivers". The papers cites as examples of how deceivers when they speak "display elevated uncertainty, share fewer details, provide more spatio-temporal details, and use less diverse and less complex language than truthtellers".

The result?

The algorithm had "modest success in classification results demonstrates that linguistic models of deception are potentially useful in discriminating deception and managerial fraud in financial statements".

Results like these are a good indication of how the audit profession can move beyond the traditional audit procedures.

Author: Malik Datardina, CPA, CA, CISA. Malik works at Auvenir as a GRC Strategist that is working to transform the engagement experience for accounting firms and their clients. The opinions expressed here do not necessarily represent UWCISA, UW, Auvenir (or its affiliates), CPA Canada or anyone else

Technology, security, analytics and innovation in the world of audit and business.

Showing posts with label audit. Show all posts

Showing posts with label audit. Show all posts

Tuesday, December 31, 2019

Monday, September 24, 2018

To appreciate blockchain, do we need to appreciate accounting and auditing first?

As an accountant, we can often forget the importance of the craft of accounting and what it meant for not just business but society.

But going back to accounting, this is how he and Paul stated the importance of accounting:

"Fibonacci’s new numbering system became a hit with the merchant class and for centuries was the preeminent source for mathematical knowledge in Europe. But something equally important also happened around this time: Europeans learned of double-entry bookkeeping, picking it up from the Arabians, who’d been using it since the seventh century. Merchants in Florence and other Italian cities began applying these new accounting measures to their daily businesses. Where Fibonacci gave them new measurement methods for business, double-entry accounting gave them a way to record it all. Then came a seminal moment: in 1494, two years after Christopher Columbus first set foot in the Americas, a Franciscan friar named Luca Pacioli wrote the first comprehensive manual for using this accounting system.

Pacioli’s Summa de arithmetica, geometria, proportioni et proportionalita, written in Italian rather than Latin so as to be more accessible to the public, would become the first popular work on math and accounting. Its section on accounting was so well received that the publisher eventually published it as its own volume. Pacioli offered access to the precision of mathematics. “Without double entry, businessmen would not sleep easily at night,” Pacioli wrote, mixing in the practical with the technical—Pacioli’s Summa would become a kind of self-help book for the merchant class.

...The Medici of Florence came first, turning themselves into vital middlemen in the matching of money flows around Europe. The Medici’s breakthrough was made possible because of their consistent use of double-entry ledgers. If a merchant in Rome wanted to sell something to a customer in Venice, these new ledgers solved the problem of trust between people who lived at great distances from each other. By debiting the payer’s bank account and crediting that of the payee—with double-entry practices—the bankers were able to, in effect, move money without having to ship physical coins. In so doing, they transformed the whole enterprise of payments, setting the stage for the Renaissance and for modern capitalism itself. Just as important, they also established the 500-year practice of bankers creating an essential role for themselves as society’s centralized trust bearers.

The value of double-entry bookkeeping, therefore, wasn’t merely in dry efficiency. The ledger came to be viewed as a kind of moral compass, whose use conferred moral rectitude on all involved with it. The merchant was pious, the banker had sanctity—three popes in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries came from the Medici family—and the trader discharged his business with veneration. Businessmen, previously mistrusted, became moral, upstanding pillars of the community. Aho writes: “Methodist Church founder John Wesley, Daniel DeFoe, Samuel Pepys, Baptist evangelicals, the deist Benjamin Franklin, the Shakers, Harmony Society, and more recently, the Iona Community in Britain, all insist that the keeping of meticulous financial accounts is part and parcel of a more general program of honesty, orderliness, and industriousness.”

Thanks to mathematical concepts imported from the Middle East during the Crusades, accounting became the moral grounding for the rise of modern capitalism, and the bean counters of capitalism became the priests of a new religion. Most (though certainly not all) people today have a hard time seeing the Bible as literal truth; but they had no trouble seeing Lehman Brothers’ books as literal truth—until the gaping inconsistencies were exposed.

The great irony of 2008 was that our belief in a system of accounting, a belief woven so deeply inside our collective psyche that we’re not even aware of it, made us vulnerable to fraud. Even when done honestly, accounting is sometimes little more than an educated guess. Modern accounting, especially at the big, international banks, has become so convoluted that it is virtually useless. In a comprehensive dissection in 2014, the Bloomberg columnist Matt Levine explained how a bank’s balance sheet is almost impossibly opaque. The “value” of a large portion of the assets on that balance sheet, he noted, is simply based on guesses made by the bank about the collectability of the loans they make, or of the bonds they hold, and the prices that they might fetch on the market, all measured against the offsetting and equally fuzzy valuation of their liabilities and obligations. If a guess is off by even 1 percent, it can turn a quarterly profit into a loss. Guessing whether a bank is actually profitable is like a pop quiz. “I submit to you that there is no answer to the quiz,” he wrote. “It is not possible for a human to know whether Bank of America made money or lost money last quarter.” A bank’s balance sheet, he said, is essentially a series of “reasonable guesses about valuation.” Make the wrong guesses, as Lehman and other troubled banks did, and you end up out of business.

Our goal here is not to trash double-entry bookkeeping or the banks. Were we to, you know, add up all the debits and credits, double-entry bookkeeping has done more good than harm. The goal really is to show the deep historical and cultural roots behind why we trusted this kind of accounting. The question now, in the wake of our fall, is whether a particular technology that allows a different kind of bookkeeping will help us renew our trust in our economic system. Can a blockchain, which is continuously open to public inspection and guaranteed not by a single bank but by a series of mathematically secured entries into a ledger that’s shared and maintained by many different computers, help us rebuild our lost social capital?"

Source: Vigna, Paul and Casey, Michael The Truth Machine: The Blockchain and the Future of Everything (p. 26-29). St. Martin's Press. Kindle Edition.

Reading this, a few things jumped out:

And was it an accountant who pointed this out to me?

No, it wasn't. It was actually blockchain enthusiasts who drew a straight line between the role accounting plays and the role blockchain could play.

No, it wasn't. It was actually blockchain enthusiasts who drew a straight line between the role accounting plays and the role blockchain could play.

In preparation for a presentation on blockchain, I wanted to refresh my mind around all things blockchain and so I was going through the audiobook, The Truth Machine, by Paul Vigna and Michale Casey. These are the two same authors who wrote the Age of Cryptocurrency. (At that time, both were Wall Street Journal reports, but Michael Casey since that publication actually decided to leave his 23-year career in journalism to focus on blockchain full time at MIT.)

And it was during this book that I was reintroduced to how important accounting was in terms of societal governance as it relates to the administering resources.

Michael Casey in this lightning talk speaks to how blockchain now offers the possibility to deliver the necessary accounting to deal with the "tragedy-of-commons-type problems" that emerge in Capitalist societies that promote self-interest above the common good and all else.

But going back to accounting, this is how he and Paul stated the importance of accounting:

"Fibonacci’s new numbering system became a hit with the merchant class and for centuries was the preeminent source for mathematical knowledge in Europe. But something equally important also happened around this time: Europeans learned of double-entry bookkeeping, picking it up from the Arabians, who’d been using it since the seventh century. Merchants in Florence and other Italian cities began applying these new accounting measures to their daily businesses. Where Fibonacci gave them new measurement methods for business, double-entry accounting gave them a way to record it all. Then came a seminal moment: in 1494, two years after Christopher Columbus first set foot in the Americas, a Franciscan friar named Luca Pacioli wrote the first comprehensive manual for using this accounting system.

Pacioli’s Summa de arithmetica, geometria, proportioni et proportionalita, written in Italian rather than Latin so as to be more accessible to the public, would become the first popular work on math and accounting. Its section on accounting was so well received that the publisher eventually published it as its own volume. Pacioli offered access to the precision of mathematics. “Without double entry, businessmen would not sleep easily at night,” Pacioli wrote, mixing in the practical with the technical—Pacioli’s Summa would become a kind of self-help book for the merchant class.

...The Medici of Florence came first, turning themselves into vital middlemen in the matching of money flows around Europe. The Medici’s breakthrough was made possible because of their consistent use of double-entry ledgers. If a merchant in Rome wanted to sell something to a customer in Venice, these new ledgers solved the problem of trust between people who lived at great distances from each other. By debiting the payer’s bank account and crediting that of the payee—with double-entry practices—the bankers were able to, in effect, move money without having to ship physical coins. In so doing, they transformed the whole enterprise of payments, setting the stage for the Renaissance and for modern capitalism itself. Just as important, they also established the 500-year practice of bankers creating an essential role for themselves as society’s centralized trust bearers.

The value of double-entry bookkeeping, therefore, wasn’t merely in dry efficiency. The ledger came to be viewed as a kind of moral compass, whose use conferred moral rectitude on all involved with it. The merchant was pious, the banker had sanctity—three popes in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries came from the Medici family—and the trader discharged his business with veneration. Businessmen, previously mistrusted, became moral, upstanding pillars of the community. Aho writes: “Methodist Church founder John Wesley, Daniel DeFoe, Samuel Pepys, Baptist evangelicals, the deist Benjamin Franklin, the Shakers, Harmony Society, and more recently, the Iona Community in Britain, all insist that the keeping of meticulous financial accounts is part and parcel of a more general program of honesty, orderliness, and industriousness.”

Thanks to mathematical concepts imported from the Middle East during the Crusades, accounting became the moral grounding for the rise of modern capitalism, and the bean counters of capitalism became the priests of a new religion. Most (though certainly not all) people today have a hard time seeing the Bible as literal truth; but they had no trouble seeing Lehman Brothers’ books as literal truth—until the gaping inconsistencies were exposed.

The great irony of 2008 was that our belief in a system of accounting, a belief woven so deeply inside our collective psyche that we’re not even aware of it, made us vulnerable to fraud. Even when done honestly, accounting is sometimes little more than an educated guess. Modern accounting, especially at the big, international banks, has become so convoluted that it is virtually useless. In a comprehensive dissection in 2014, the Bloomberg columnist Matt Levine explained how a bank’s balance sheet is almost impossibly opaque. The “value” of a large portion of the assets on that balance sheet, he noted, is simply based on guesses made by the bank about the collectability of the loans they make, or of the bonds they hold, and the prices that they might fetch on the market, all measured against the offsetting and equally fuzzy valuation of their liabilities and obligations. If a guess is off by even 1 percent, it can turn a quarterly profit into a loss. Guessing whether a bank is actually profitable is like a pop quiz. “I submit to you that there is no answer to the quiz,” he wrote. “It is not possible for a human to know whether Bank of America made money or lost money last quarter.” A bank’s balance sheet, he said, is essentially a series of “reasonable guesses about valuation.” Make the wrong guesses, as Lehman and other troubled banks did, and you end up out of business.

Our goal here is not to trash double-entry bookkeeping or the banks. Were we to, you know, add up all the debits and credits, double-entry bookkeeping has done more good than harm. The goal really is to show the deep historical and cultural roots behind why we trusted this kind of accounting. The question now, in the wake of our fall, is whether a particular technology that allows a different kind of bookkeeping will help us renew our trust in our economic system. Can a blockchain, which is continuously open to public inspection and guaranteed not by a single bank but by a series of mathematically secured entries into a ledger that’s shared and maintained by many different computers, help us rebuild our lost social capital?"

Source: Vigna, Paul and Casey, Michael The Truth Machine: The Blockchain and the Future of Everything (p. 26-29). St. Martin's Press. Kindle Edition.

Reading this, a few things jumped out:

- Double-entry accounting actually was invented by "Arabs": As the authors noted above, "Europeans learned of double-entry bookkeeping, picking it up from the Arabians, who’d been using it since the seventh century". Going through accounting, this was the first that I heard of this, but it's not surprising given the Islamic world led the globe in terms of science and technology for a few centuries.

- The link between ethics/integrity and accounting was established at the inception: "The value of double-entry bookkeeping, therefore, wasn’t merely in dry efficiency. The ledger came to be viewed as a kind of moral compass, whose use conferred moral rectitude on all involved with it. The merchant was pious, the banker had sanctity—three popes in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries came from the Medici family—and the trader discharged his business with veneration. Businessmen, previously mistrusted, became moral, upstanding pillars of the community. Aho writes: “Methodist Church founder John Wesley, Daniel DeFoe, Samuel Pepys, Baptist evangelicals, the deist Benjamin Franklin, the Shakers, Harmony Society, and more recently, the Iona Community in Britain, all insist that the keeping of meticulous financial accounts is part and parcel of a more general program of honesty, orderliness, and industriousness.”" Although it's quite far to say that accountants are any kind of priest, there is a level of "financial asceticism" in terms of abstaining from investments to be able to have the objectivity required to complete financial audits. Furthermore, the profession needs to assess to the degree we are investing in this cornerstone of the profession. More thought needs to be given as to how much of threat the "post-truth era" is on the profession. If society continues to feel there is no such thing as truth, then the ability to act as an anchor of integrity is limited.

- Pervasive importance of accounting to the functioning of society: When expressing the value of financial accounting and auditing, people seem to take it for granted forgetting that if there was no way to inspect the confidential books of companies that "game theory" would take over. In a sense, the "tragedy of the commons" that is addressed by financial audits is ensuring managers don't lie when claiming that they made profits of this much and have assets of that much. That is, without audits there would be no way to trust management as the financial fraud that we see wouldn't be limited to a few players but be much more pervasive.

- People will blame accountants even though we are just recordkeepers: The authors call out accounting stating that: "Modern accounting, especially at the big, international banks, has become so convoluted that it is virtually useless". Accounting is the art and science of communicating the economic reality of entities to allow people to make investment decisions. It is a complex function of navigating competing opinions on how to accurately report on things. I think it's ironic that the book notes a few pages later on how Bitcoin Classic had to separate (or fork) from Bitcoin Cash because the two factions couldn't agree on the memory size of the protocol. When it comes to accounting standards there is no forking: all must agree on a common set of accounting standards to be used for financial reporting. Furthermore, the problems that lay with the banking system really can't be blamed on financial reporting but stem from the reality that capital runs the world - even if it means running over the truth once in a while.

With respect to the last point, it is important for blockchainthusiasts to keep in mind that standards are really at the heart of blockchain. Traditionally, setting the standard has always been hard because Capitalism promotes freedom, and so people are incentivized to get away from standards! It's hard enough when you have people trying to simply codify something, let alone trying to create decentralized distributed ledger that will be intolerant of any unauthentic interpretations. But we will delve into this in future posts.

Author: Malik Datardina, CPA, CA, CISA. Malik works at Auvenir as a GRC Strategist that is working to transform the engagement experience for accounting firms and their clients. The opinions expressed here do not necessarily represent UWCISA, UW, Auvenir (or its affiliates), CPA Canada or anyone else

Friday, November 3, 2017

Big Data Auditing Revisited: Context is King

It has been a few years since I wrote up on Big Data and the Audit. It was one of the more popular posts with over a 1,000 hits to date.

The post looks at Big Data: A Revolution That Will Transform How We Live, Work, and Think by Kenneth Cukier and Viktor Mayer-Schönberger. I enjoyed the book as it really broke down the business impact of big data without getting in technical details of the underlying technology.

The post looks at Big Data: A Revolution That Will Transform How We Live, Work, and Think by Kenneth Cukier and Viktor Mayer-Schönberger. I enjoyed the book as it really broke down the business impact of big data without getting in technical details of the underlying technology.

Why take a second look at big data auditing?

Big data and the accompanying analytical models are key a precursor to artificial intelligence. Machine learning algorithms that power the AI bots requires the users to analyse the problem and teach the underlying algorithm.Part 1: Context is King

To make things a bit more digestible, I thought it would be good to divide the post into two parts. The first post is more palatable as I want to explore the second use case in a bit more detail and its relevance to today. The second post will be a bit more controversial as I will take a look at the difficulty of applying fraud or cancer-fighting algorithms in the realm of (external) financial audit.

But let's look at the first issue: how can big data analytics give us better context?

In the original post, I spoke discussed the use case used in Cukier and Mayer-Schönberger's work around Inrix. The book gives the example of how an investment firm is using traffic analysis, from Inrix, to determine the sales that a retailer will make and then buy or sell the stock of the retailer on that information. In a sense, the investment is using vehicular traffic as a proxy for sales. In an audit context, auditors can develop expectations of what sales should be based on the number of vehicles going around stores. For example, if sales are going up, but the number of vehicles are going down then the auditor would need to take a closer look.

What I realized from this example is that what big data can give auditors better context around things and assess reasonability of things. That is as more sensor data and other data are available to auditors to integrate into statistical models, the more they will be able to spot anomalies.

What I realized from this example is that what big data can give auditors better context around things and assess reasonability of things. That is as more sensor data and other data are available to auditors to integrate into statistical models, the more they will be able to spot anomalies.

One of the issues with Barry Minkow's ZZZBest accounting fraud was the lack of context. For more on the fraud, check this video:

I actually studied this case in my auditing class at the University of Waterloo. One of the lessons we were take away from this case was that the auditors didn't know how much a site restoration would cost on average (see the first bullet in this text on page 129). But how would an auditor be able to access such data? Even with the advent of the internet, it is not simply a matter of Googling for the information.

More recently, an accounting professor was found to have generated data fraudulently. The way he got caught was that a statistic he used didn't correspond to reality. Specifically:

"misrepresented the number of U.S.-based offices it had: not 150, as the paper maintained (and as a reader had noticed might be on the high side, triggering an inquiry from the journal)" [Emphasis added]

More recently, an accounting professor was found to have generated data fraudulently. The way he got caught was that a statistic he used didn't correspond to reality. Specifically:

"misrepresented the number of U.S.-based offices it had: not 150, as the paper maintained (and as a reader had noticed might be on the high side, triggering an inquiry from the journal)" [Emphasis added]

Again, the reader had the context to understand what was presented was unreasonable causing the study to unravel and exposing the academic fraud perpetrated by Hunton.

What will it take to make this a reality?

What's missing is a data aggregation tool that can connect to the private, third party, and public data feeds that an auditor can leverage for statistical analysis. Furthermore, for this to be useful to clients and the business community large are visualized depictions that enable the auditor to tell the story in a better way rather than handing over complex spreadsheets.

Of course for auditors to present such materials requires them to have deeper training in data wrangling, statistics and visualization tools and techniques.

In the next post, we will revisit the first use case that I presented in the original post that explored how the New York City was better able to audit illegal conversions through the use of big data analytical techniques. Originally, I had thought this would be a good model to apply in the world of audit. However, I am revisiting this idea.

Author: Malik Datardina, CPA, CA, CISA. Malik works at Auvenir as a GRC Strategist that is working to transform the engagement experience for accounting firms and their clients. The opinions expressed here do not necessarily represent UWCISA, UW, Auvenir (or its affiliates), CPA Canada or anyone else

Monday, October 2, 2017

What can driving algorithms tell us about robo-auditors?

On a recent trip to the US, decided to opt for a vehicle with the sat-nav as I was going to need directions and wanted to save on the roaming charges. I normally rely on Google Maps for guiding me around traffic jams but thought that the sat-nav would be a good substitute.

Unfortunately, it took me on a wild goose chase more than once – to avoid the traffic. I had blindly followed the algorithm's suggestions assuming it would save me time. I ended up being stuck at traffic lights waiting to a left-turn for what seemed like forever.

Then I realized that I was missing was that feature in Google Maps that tells you how much time you will save by taking the path less traveled. If it only saves me a few minutes, I normally stick to the highway as there are no traffic lights and things may clear-up. Effectively, what Google does is that it gives a way to supervise it’s algorithmic decision-making process.

How does this help with understanding the future of robot auditors?

Algorithms, and AI robots more broadly, need to give sufficient data to judge whether the algorithm is driving in the right direction. Professional auditing standards currently require supervision of junior staff – but the analogy can be applied to AI-powered audit-bots. For example, let’s say there is an AI auditor assessing the effectiveness of access controls and it’s suggesting to not rely on the control. The supervisory data needs to give enough context to assess what the consequences of taking such a decision and the alternative. This could include:

What UI does the auditor need to run algorithmic audit?

On a broader note, what is the user interface (UI) to capture this judgment and enable such supervision?

Visualization (e.g. the vehicle moving on the map), mobile technology, satellite navigation and other technologies are assembled to guide the driver. Similarly, auditors need a way to pull together the not just the data necessary to answer the questions above but also a way to understand what risks within the audit require greater attention. This will help the auditor understand where the audit resources need to be allocated from nature, extent and timing perspective.

We all feel a sense of panic when reading the latest study that predict the pending robot-apocalypse in the job market. The reality is that even driving algos need supervision and cannot wholly be trusted on their own. Consequently, when it comes to applying algorithms and AI to audits, it’s going to take some serious effort to define the map that enables such automation let alone building that automation itself.

Author: Malik Datardina, CPA, CA, CISA. Malik works at Auvenir as a GRC Strategist that is working to transform the engagement experience for accounting firms and their clients. The opinions expressed here do not necessarily represent UWCISA, UW, Auvenir (or its affiliates), CPA Canada or anyone else

Unfortunately, it took me on a wild goose chase more than once – to avoid the traffic. I had blindly followed the algorithm's suggestions assuming it would save me time. I ended up being stuck at traffic lights waiting to a left-turn for what seemed like forever.

Then I realized that I was missing was that feature in Google Maps that tells you how much time you will save by taking the path less traveled. If it only saves me a few minutes, I normally stick to the highway as there are no traffic lights and things may clear-up. Effectively, what Google does is that it gives a way to supervise it’s algorithmic decision-making process.

How does this help with understanding the future of robot auditors?

Algorithms, and AI robots more broadly, need to give sufficient data to judge whether the algorithm is driving in the right direction. Professional auditing standards currently require supervision of junior staff – but the analogy can be applied to AI-powered audit-bots. For example, let’s say there is an AI auditor assessing the effectiveness of access controls and it’s suggesting to not rely on the control. The supervisory data needs to give enough context to assess what the consequences of taking such a decision and the alternative. This could include:

- Were controls relied on in previous years? This would give some context as to whether this recommendation is in-line with prior experience.

- What are the results of other security controls? This would give an understanding whether this is actually an anomaly or part of the same pattern of an overall bad control environment.

- How close is it between the reliance and non-reliance decision? Perhaps this is more relevant in the opposite situation where the system is saying to rely on controls when it has found weaknesses. However, either way the auditor should understand how close it is to make the opposite judgment.

- What is the impact on substantive test procedures? If access controls are not relied on, the impact on substantive procedures needs to be understood.

- What alternative procedures that can be relied on? Although in this scenario the algo is telling us the control is reliable, in a scenario where it would recommend not relying on such a control.

What UI does the auditor need to run algorithmic audit?

On a broader note, what is the user interface (UI) to capture this judgment and enable such supervision?

Visualization (e.g. the vehicle moving on the map), mobile technology, satellite navigation and other technologies are assembled to guide the driver. Similarly, auditors need a way to pull together the not just the data necessary to answer the questions above but also a way to understand what risks within the audit require greater attention. This will help the auditor understand where the audit resources need to be allocated from nature, extent and timing perspective.

We all feel a sense of panic when reading the latest study that predict the pending robot-apocalypse in the job market. The reality is that even driving algos need supervision and cannot wholly be trusted on their own. Consequently, when it comes to applying algorithms and AI to audits, it’s going to take some serious effort to define the map that enables such automation let alone building that automation itself.

Author: Malik Datardina, CPA, CA, CISA. Malik works at Auvenir as a GRC Strategist that is working to transform the engagement experience for accounting firms and their clients. The opinions expressed here do not necessarily represent UWCISA, UW, Auvenir (or its affiliates), CPA Canada or anyone else

Saturday, September 30, 2017

CPAOne: AI, Analytics and Beyond

Attended the CPA One Conference almost two weeks ago in Ottawa, Ontario. Given that my space is in audit innovation, I attended the more techno-oriented presentations. Here's a summary of the sessions that I attended:

"Big data: Realizing benefits in the age of machine learning and artificial intelligence": The session was kicked off by Oracle's Maria Pollieri. The session delved deep in the detail of machine learning and would have been beneficial to those who were trying to wrap things around thing more from a technical side. She was followed up by Roger's Jane Skoblo. She mentioned a fact that really grabbed my attention: when a business can just increase its accessibility to data by 10%; it can result in up to $65 million increase in benefits.

"Big data: Realizing benefits in the age of machine learning and artificial intelligence": The session was kicked off by Oracle's Maria Pollieri. The session delved deep in the detail of machine learning and would have been beneficial to those who were trying to wrap things around thing more from a technical side. She was followed up by Roger's Jane Skoblo. She mentioned a fact that really grabbed my attention: when a business can just increase its accessibility to data by 10%; it can result in up to $65 million increase in benefits.

The next day started with Pete's and Neeraj's session on audit automation, "Why nobody loves the audit". They want over a survey of auditors and clients on the key pain points of the external audit. It turns out that these challenges are actually shared by both. For example, clients lack context on "the why" things are being collected, while auditors found it difficult to work with clients who lacked such context. On the data side, clients have hard time gathering docs and data, while the auditors spent too much time gathering this information. From a solutions perspective, the presenters discussed how Auvenir puts a process around gathering the data and enables better communication. This will be explored in future posts when we look at process standardization as a key pre-requisite to getting AI into the audit.

The keynote on this day was delivered by Deloitte Digital's Shawn Kanungo, "The 0 to 100 effect". The session was well-received as he discussed the different aspects of exponential change and its impact on the profession (which was discussed previously here). One of the key takeaways I had from his presentation was how a lot of innovation is recombining ideas that already exist. Check this video he posted that highlights some of the points from his talk:

Also, checked out the presentation by Kevin Kolliniatis from KPMG and Chris Dulny from PwC, "AI and the evolution of the audit". Chris did a good job breaking down AI and made it digestible for the crowd. Kevin highlighted Mindbridge.ai in his presentation noting the link that AI is key for identifying unusual patterns.

That being said, the continuing challenge is how do we get data out of the systems in manner that's reliable (e.g. it's the right data, for the right period, etc.) and is understood (e.g. we don't have to go back and forth with the client to understand what they sent).

Last but not least was "Future of finance in a digital world" with Grant Abrams and Tahanie Thabet from Deloitte. They broke down how digital technologies are reshaping the way the finance department. As I've expressed here, one of the keys is to appreciate the difference between AI and Robotic Process Automation (RPA). So I thought it was really beneficial that they actually showed how such automation can assist with moving data from invoices into the system (the demo was slightly different than the one that can be seen below, but illustrates the potential of RPA). They didn't get into a lot of detail on blockchain but mentioned it is relevant to the space (apparently they have someone in the group that specifically tackles these types of conversations).

Kudos to CPA Canada for tackling these leading-edge topics! Most of these sessions were well attended and people asked questions wanting to know more. It's through these types of open forums that CPAs can learn to embrace the change that we all know is coming.

Author: Malik Datardina, CPA, CA, CISA. Malik works at Auvenir as a GRC Strategist that is working to transform the engagement experience for accounting firms and their clients. The opinions expressed here do not necessarily represent UWCISA, UW, Auvenir (or its affiliates), CPA Canada or anyone else

Also, checked out the presentation by Kevin Kolliniatis from KPMG and Chris Dulny from PwC, "AI and the evolution of the audit". Chris did a good job breaking down AI and made it digestible for the crowd. Kevin highlighted Mindbridge.ai in his presentation noting the link that AI is key for identifying unusual patterns.

That being said, the continuing challenge is how do we get data out of the systems in manner that's reliable (e.g. it's the right data, for the right period, etc.) and is understood (e.g. we don't have to go back and forth with the client to understand what they sent).

Last but not least was "Future of finance in a digital world" with Grant Abrams and Tahanie Thabet from Deloitte. They broke down how digital technologies are reshaping the way the finance department. As I've expressed here, one of the keys is to appreciate the difference between AI and Robotic Process Automation (RPA). So I thought it was really beneficial that they actually showed how such automation can assist with moving data from invoices into the system (the demo was slightly different than the one that can be seen below, but illustrates the potential of RPA). They didn't get into a lot of detail on blockchain but mentioned it is relevant to the space (apparently they have someone in the group that specifically tackles these types of conversations).

Kudos to CPA Canada for tackling these leading-edge topics! Most of these sessions were well attended and people asked questions wanting to know more. It's through these types of open forums that CPAs can learn to embrace the change that we all know is coming.

Author: Malik Datardina, CPA, CA, CISA. Malik works at Auvenir as a GRC Strategist that is working to transform the engagement experience for accounting firms and their clients. The opinions expressed here do not necessarily represent UWCISA, UW, Auvenir (or its affiliates), CPA Canada or anyone else

Labels:

2017,

AI,

Artificial Intelligence,

audit,

automation,

automation of knowledge work,

Auvenir,

blockchain,

CPA Canada,

CPA One,

Deloitte,

Deloitte Digital,

KPMG,

Oracle,

PWC,

robot,

robotic process automation,

RPA

Sunday, June 18, 2017

"Bitcoin process flow": Accountant's guide to risk & controls around the blockchain

For the past year, I have been following blockchain to assess how this exponential technology will impact financial auditing.

Unlike artificial intelligence, quantum computing, or virtual reality, this technology addresses the heart of accounting profession: it is an innovation in the process of recording and accounting for transactions. Furthermore, it captures "proof of interaction" by leveraging digital signatures as the basis for executing exchanges. Both these features speaks to the core of what we do as accountants and auditors.

But before we get ahead of ourselves, it is important to look at blockchain in a nuanced way. On the one hand, technologists should be careful about how the blockchain will impact the audit. However, at the same time, the audit profession can't afford to ignore it. To do so would invite the profession to repeat the mistakes of Kodak who, despite inventing the digital camera in 1975, were ultimately disrupted by that very same technology.

Part of the problem was understanding that digital technology was changing at a linear pace instead of an exponential pace. In this post, Peter Diamandis talks about how "30 exponential steps" compares to "30 exponential steps" (and talks more broadly about linear vs exponential thinking). Ray Kurzweil, the infamous Googler, talks about the infamous story of how the inventor of chess requested an exponential amount of rice (and is rumored to have lost his head).

Going back to looking at this as an auditor, I think a useful starting point to understand the topic of blockchain is one of "professional skepticism". Specifically,:

Unlike artificial intelligence, quantum computing, or virtual reality, this technology addresses the heart of accounting profession: it is an innovation in the process of recording and accounting for transactions. Furthermore, it captures "proof of interaction" by leveraging digital signatures as the basis for executing exchanges. Both these features speaks to the core of what we do as accountants and auditors.

But before we get ahead of ourselves, it is important to look at blockchain in a nuanced way. On the one hand, technologists should be careful about how the blockchain will impact the audit. However, at the same time, the audit profession can't afford to ignore it. To do so would invite the profession to repeat the mistakes of Kodak who, despite inventing the digital camera in 1975, were ultimately disrupted by that very same technology.

Part of the problem was understanding that digital technology was changing at a linear pace instead of an exponential pace. In this post, Peter Diamandis talks about how "30 exponential steps" compares to "30 exponential steps" (and talks more broadly about linear vs exponential thinking). Ray Kurzweil, the infamous Googler, talks about the infamous story of how the inventor of chess requested an exponential amount of rice (and is rumored to have lost his head).

Going back to looking at this as an auditor, I think a useful starting point to understand the topic of blockchain is one of "professional skepticism". Specifically,:

Why would people trust this?

It's been quite the task in trying to understand how the public blockchain, specifically bitcoin, works in disintermediating centralized authorities, such as banks, to settle transactions between two parties that don't know each other. In a sense, a retailer, like Overstock.com, only needs to receive a string of digits, such as:

https://blockchain.info/block/0000000000000002f7de2a020d4934431bf1dc4b75ef11eed2eede55249f0472 and be satisfied that the purchaser has bitcoins required to buy the merchandise and hasn't already spent them. That is, they have "assurance" from the above string of digits and characters that the sender has not already spent the bitcoin or has simultaneously sent the bitcoins to someone else.

The following video illustrates the peer-to-peer nature of the ledger:

This video gives a good 5-minute summary delving more into the technical details of bitcoin. If you need more, check out this 22-minute video by the same author.

The following video by Andreas Antonpolous, is especially helpful in understanding how the blockchain works at a deeper level. Encourage watching the whole video, but if you want to get to the meat of how the Proof of Work, SHA hash function works, skip to this point in the video .

As noted in these videos, when you send or receive bitcoins there's no exchange of actual digital code. Rather, it merely updates on the ledgers across the bitcoin network. It's quite ironic for us accountants - the way to bitcoin holdings are really just the sum of the person's bitcoin transactions.

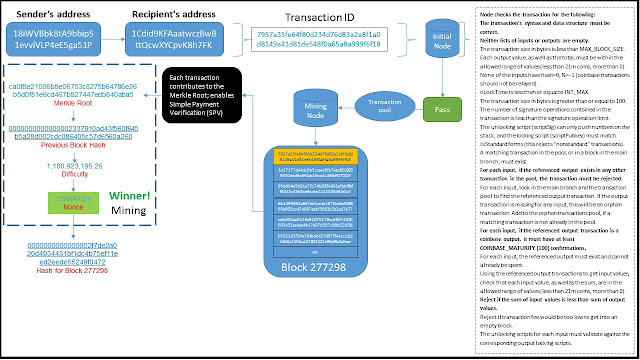

The bitcoin transaction that I used to perform the walk-through is the same one used in the book and it belongs to block #277298. As per the book, Alice sends 0.015 bitcoins to Bob's cafe to buy a coffee.

Process:

For those bold enough to transact in bitcoin, they need to set-up a bitcoin wallet on their computer or mobile phone. Most important of all this needs to be secured as it holds your private key that is used to sign the transactions and send over to others. If this key is compromised, lost, etc. - you will lose all your bitcoins! And unlike credit cards, there is no central authority to complain to if this happens.

If you live in Toronto, you can actually buy the bitcoins at Deloitte at Bay and Adelaide (but you will need to set-up your digital wallet before doing this).

It cannot be overstated enough that this is where the bulk of security issues occur and makes bitcoin prone to hacking. As noted in this article, the August 2016 hack of Bitfinex had to do with the way that the actual wallets are secured using multi-signature wallets where multiple parties (user, Bitfinex, and Bitgo) held the keys. It should be clear, however, that it's not the actual ledger that is being hacked or more accurately being modified. Instead, it's the encryption keys that are being stolen by the attackers.

How did the thieves access the funds given that the ledger is reporting all transactions publicly?

This article from the Verge gives some insights on how bitcoins can be effectively laundered out of the blockchain.

Process: In this example, Alice is sending the bitcoins to Bob's public key "1Cdid9KFAaatwczBwBttQcw XYCpvK8h7FK", which is also known as his bitcoin address.

If you want to wade into the details as to how the transaction is set-up and transmitted check out these two posts (here and here) by Google engineer, Ken Shirrif.

Risks: Unauthorized recipient is sent the bitcoin. Unauthorized user modifies the payments.

Controls: Public key-cryptography: As noted in the process, Alice must send the bitcoin to Bob's bitcoin address or his public key. As long as she is 100% sure that it is actually Bob's address then only Bob will be able to access those bitcoins. In this scenario, Alice will likely scan Bob's QR since she is buying the coffee from him. However, if this were an online transaction then she would need to use an alternative method to verify that she is sending her bitcoins to the right address. PKI also ensures that the message can't be altered.

Process:After the bitcoins are sent to the recipient a transaction identification number is generated, which in this case is “7957a35fe64f80d234d76d83a2a8f1a0d8149a41d81de548f0a65a8a999f6f18”.

Risks: Transaction will not be properly identified.

Control: Each bitcoin transaction is uniquely identified by transaction identification.

Process: Transaction is captured by the initial node. Risk:Transaction will be invalid, incomplete, incorrectly formatted, or violate other rules within the bitcoin protocol. See below for how these controls would be classified as “input edit controls” or data validation routine.

Risks: Inaccurate, invalid or incomplete transaction or transaction details will be posted to the blockchain.

Controls: The following list of controls are taken verbatim from chapter 8 Antonopolous's book mentioned earlier (or click here to see "Independent Verification of Transactions" in chapter 8)

Validity checks.The real genius of bitcoin is that it ensures that the person sending you the bitcoin already has them. In other words, it’s provide comfort on the existence assertion – to potential vendor or other person that will receive those bitcoins. With respect to data validations, it provides the following checks:· None of the inputs have hash=0, N=–1 (coinbase transactions should not be relayed).

Range checks. The following controls ensure that the values submitted are within an acceptable range. The last one is what prohibits the mining of coins beyond the 21 million limit set by the protocol:

Process: If the transaction meets the criteria then it is passed on to the miners to be mined in a block. Otherwise the transaction is rejected.

Risk/Control: this is a flow through from the previous step.

Process: The transaction is then sent to a pool to be mined. The protocol looks to have the transaction mined within 10 minutes. When the sender submits the transaction to the recipient, they can add fees to be paid to the miners. However, those do not give fees are of a lower priority than the people that actually paying to have their transactions processed. Right now this is not critical as the main reward is getting awarded 12.5 bitcoins for mining (i.e. guessing the correct nonce which is discussed below). When bitcoins run out in 2040, however, it is these transaction fees that will become the main “remuneration” for the miners.

Risk: Miners incentives will not be aligned with verifying transactions.

Control: The economic incentives give the miners a reason not to counterfeit. It is less work to actually mine the coin then try to counterfeit the coin by amassing the necessary computer power. Also, the problem for profit-seeking criminals is that once they counterfeit the coins (e.g. through the 51% attack) then the community would lose faith in the bitcoin making it worthless. However, this does not stop non-profit seeking parties who are looking for a challenge or to destroy the bitcoin platform.

Risk: Any node can verify the integrity of the blockchain by downloading the full blockchain ledger and ensuring that one block is linked to the previous block. However, to do this you need about 100 GB and a few days to download the blockchain. Consequently, there is a potential risk that mobile devices - which are used by most to execute bitcoin transactions - is unable to do this verification because it lacks the storage capacity and processing power to verify the blockchain.

https://blockchain.info/block/0000000000000002f7de2a020d4934431bf1dc4b75ef11eed2eede55249f0472 and be satisfied that the purchaser has bitcoins required to buy the merchandise and hasn't already spent them. That is, they have "assurance" from the above string of digits and characters that the sender has not already spent the bitcoin or has simultaneously sent the bitcoins to someone else.

Part 1: Background on the process flow

Before going through the walk through, it is important to watch these videos first to get some background on how Bitcoin works.The following video illustrates the peer-to-peer nature of the ledger:

This video gives a good 5-minute summary delving more into the technical details of bitcoin. If you need more, check out this 22-minute video by the same author.

The following video by Andreas Antonpolous, is especially helpful in understanding how the blockchain works at a deeper level. Encourage watching the whole video, but if you want to get to the meat of how the Proof of Work, SHA hash function works, skip to this point in the video .

As noted in these videos, when you send or receive bitcoins there's no exchange of actual digital code. Rather, it merely updates on the ledgers across the bitcoin network. It's quite ironic for us accountants - the way to bitcoin holdings are really just the sum of the person's bitcoin transactions.

Part 2: Walk-through of a Bitcoin Transaction

I originally mapped out this "walk-through" of a bitcoin transaction in PowerPoint. The transaction is largely based on the book, Mastering Bitcoin, by Andreas Antonopolous (same individual in the video above). He has been nice enough to make a number of the chapters online, including chapter 2, 5 and 8 that I used to develop this flow.The bitcoin transaction that I used to perform the walk-through is the same one used in the book and it belongs to block #277298. As per the book, Alice sends 0.015 bitcoins to Bob's cafe to buy a coffee.

Step 1: Get a bitcoin wallet and some bitcoin.

Process:

For those bold enough to transact in bitcoin, they need to set-up a bitcoin wallet on their computer or mobile phone. Most important of all this needs to be secured as it holds your private key that is used to sign the transactions and send over to others. If this key is compromised, lost, etc. - you will lose all your bitcoins! And unlike credit cards, there is no central authority to complain to if this happens.

If you live in Toronto, you can actually buy the bitcoins at Deloitte at Bay and Adelaide (but you will need to set-up your digital wallet before doing this).

It cannot be overstated enough that this is where the bulk of security issues occur and makes bitcoin prone to hacking. As noted in this article, the August 2016 hack of Bitfinex had to do with the way that the actual wallets are secured using multi-signature wallets where multiple parties (user, Bitfinex, and Bitgo) held the keys. It should be clear, however, that it's not the actual ledger that is being hacked or more accurately being modified. Instead, it's the encryption keys that are being stolen by the attackers.

How did the thieves access the funds given that the ledger is reporting all transactions publicly?

This article from the Verge gives some insights on how bitcoins can be effectively laundered out of the blockchain.

Step 2: Send bitcoins to the recipient.

Process: In this example, Alice is sending the bitcoins to Bob's public key "1Cdid9KFAaatwczBwBttQcw XYCpvK8h7FK", which is also known as his bitcoin address.

If you want to wade into the details as to how the transaction is set-up and transmitted check out these two posts (here and here) by Google engineer, Ken Shirrif.

Risks: Unauthorized recipient is sent the bitcoin. Unauthorized user modifies the payments.

Controls: Public key-cryptography: As noted in the process, Alice must send the bitcoin to Bob's bitcoin address or his public key. As long as she is 100% sure that it is actually Bob's address then only Bob will be able to access those bitcoins. In this scenario, Alice will likely scan Bob's QR since she is buying the coffee from him. However, if this were an online transaction then she would need to use an alternative method to verify that she is sending her bitcoins to the right address. PKI also ensures that the message can't be altered.

Step 3: Generate the transaction ID

Process:After the bitcoins are sent to the recipient a transaction identification number is generated, which in this case is “7957a35fe64f80d234d76d83a2a8f1a0d8149a41d81de548f0a65a8a999f6f18”.

Risks: Transaction will not be properly identified.

Control: Each bitcoin transaction is uniquely identified by transaction identification.

Step 4: Perform checks at the node

Process: Transaction is captured by the initial node. Risk:Transaction will be invalid, incomplete, incorrectly formatted, or violate other rules within the bitcoin protocol. See below for how these controls would be classified as “input edit controls” or data validation routine.

Risks: Inaccurate, invalid or incomplete transaction or transaction details will be posted to the blockchain.

Controls: The following list of controls are taken verbatim from chapter 8 Antonopolous's book mentioned earlier (or click here to see "Independent Verification of Transactions" in chapter 8)

Validity checks.The real genius of bitcoin is that it ensures that the person sending you the bitcoin already has them. In other words, it’s provide comfort on the existence assertion – to potential vendor or other person that will receive those bitcoins. With respect to data validations, it provides the following checks:· None of the inputs have hash=0, N=–1 (coinbase transactions should not be relayed).

- A matching transaction in the pool, or in a block in the main branch, must exist.

- For each input, if the referenced output exists in any other transaction in the pool, the transaction must be rejected.

- For each input, look in the main branch and the transaction pool to find the referenced output transaction. If the output transaction is missing for any input, this will be an orphan transaction. Add to the orphan transactions pool, if a matching transaction is not already in the pool.

- For each input, if the referenced output transaction is a coinbase output, it must have at least COINBASE_MATURITY (100) confirmations.

- For each input, the referenced output must exist and cannot already be spent.

- Reject if transaction fee would be too low to get into an empty block.

- The unlocking scripts for each input must validate against the corresponding output locking scripts.

- The transaction’s syntax and data structure must be correct.

- Neither lists of inputs or outputs are empty.

- The transaction size in bytes is less than MAX_BLOCK_SIZE.

- The transaction size in bytes is greater than or equal to 100.

- The number of signature operations contained in the transaction is less than the signature operation limit

- The unlocking script (scriptSig) can only push numbers on the stack, and the locking script (scriptPubkey) must match isStandard forms (this rejects "nonstandard" transactions)

- Reject if the sum of input values is less than sum of output values.

Range checks. The following controls ensure that the values submitted are within an acceptable range. The last one is what prohibits the mining of coins beyond the 21 million limit set by the protocol:

- nLockTime is less than or equal to INT_MAX.

- Each output value, as well as the total, must be within the allowed range of values (less than 21m coins, more than 0).

- Using the referenced output transactions to get input values, check that each input value, as well as the sum, are in the allowed range of values (less than 21m coins, more than 0).

Step 5: Accept or reject the transaction

Process: If the transaction meets the criteria then it is passed on to the miners to be mined in a block. Otherwise the transaction is rejected.

Risk/Control: this is a flow through from the previous step.

Step 6: Send transaction to be mined

Process: The transaction is then sent to a pool to be mined. The protocol looks to have the transaction mined within 10 minutes. When the sender submits the transaction to the recipient, they can add fees to be paid to the miners. However, those do not give fees are of a lower priority than the people that actually paying to have their transactions processed. Right now this is not critical as the main reward is getting awarded 12.5 bitcoins for mining (i.e. guessing the correct nonce which is discussed below). When bitcoins run out in 2040, however, it is these transaction fees that will become the main “remuneration” for the miners.

Risk: Miners incentives will not be aligned with verifying transactions.

Control: The economic incentives give the miners a reason not to counterfeit. It is less work to actually mine the coin then try to counterfeit the coin by amassing the necessary computer power. Also, the problem for profit-seeking criminals is that once they counterfeit the coins (e.g. through the 51% attack) then the community would lose faith in the bitcoin making it worthless. However, this does not stop non-profit seeking parties who are looking for a challenge or to destroy the bitcoin platform.

Step 7: Pool the transaction with other transactions to be mined.

Process: As you can see from this list of transactions, transaction ID "7957a35fe64f80d..." is just one of the many transactions that are pooled together to be mined (i.e. checked) and then added to the blockchain ledger. You can try to find the transaction by going to the link, hitting ctrl-F and pasting in the first few digits of the transaction.

Risk and Controls: NA

Step 8: Protocol uses Merkel-Tree structure to hash transactions

Process: What I found challenging was to understand how the header hash (i.e. this) links to the actual transaction (i.e. this). And that’s where my journey took me to Merkle Tree structures. What Merkle trees allow you to do is recursive hashing that combines transactions recursively into the root hash as follows:

(Taken from: here)

Control: The use of Merkle Roots enables the verification of bitcoin transactions on small devices such as smartphones. Unlike a computer that has sufficient storage, these devices can simply use merkle paths to verify the transactions instead. Using Simplified Payment Verification, the bitcoin protocol, enables you to verify that the transaction is part of this root in order to get comfort that it is part of the block that has been checked and added to the blockchain. This structure also protects the pseudonymity of the other transactions as it doesn't require decrypting the other transaction in the tree structure. This control, however, relies ultimately the overall blockchain is being verified by network and does not standalone.

Process: Miners need to generate the header of the blockhash, which consists of the previous hash, the merkle root of the current set of transactions, as well as the nonce (see step 10 and 11)

Risk: Transactions will be modified in an unauthorized manner.

Step 9: Combining the hash transactions with previous block

Process: Miners need to generate the header of the blockhash, which consists of the previous hash, the merkle root of the current set of transactions, as well as the nonce (see step 10 and 11)

Risk: Transactions will be modified in an unauthorized manner.

Control: This is what effectively puts the "chain" in blockchain. It’s ultimately this structure that prevents transactions that have been added to the ledger from being modified. So let’s say you want to alter transactions that were added 1 hour ago (remember: it takes 10 minutes to add a block of transactions) you have to change the following:

- Merkle root of the hash of that transaction that was added 60 minutes ago.

- The header hash of the transaction of the block that was added 50 minutes ago.

- The header hash of the transaction of the block that was added 40 minutes ago.

- The header hash of the transaction of the block that was added 30 minutes ago.

- The header hash of the transaction of the block that was added 20 minutes ago.

- The header hash of the transaction of the block that was added 10 minutes ago.

Why?

Because each hash is based on the hash of that transaction that was added an hour ago. Any modification of that hash alters each of the 5 blocks that comes after that. Each block of the 5 block’s data structure depends on that hash-value of that transaction you want to modify.

Process: The difficulty is actually set by the peer-to-peer system itself reviewing that the average time for the last 2016 blocks was 10 minutes on average. If not, then the difficulty will be adjusted up or down to get to the 10 minute average.

Risk: Transactions will be mined in an untimely manner; i.e. more or less than 10 minutes.

Control: The difficulty/target effectively as a throttle to ensure that the blocks mined takes 10 minutes regardless the number the miners or the computers involved(i.e. which will continually fluctuate). What the target determines is the level of guessing that the miners have to do find the "nonce" (see next step). The lower the target the more difficult it is to guess that number because there are possibilities of the answer being correct.

Antonopoulos, in Mastering Bitcoin, gives the following analogy:

"To give a simple analogy, imagine a game where players throw a pair of dice repeatedly, trying to throw less than a specified target. In the first round, the target is 12. Unless you throw double-six, you win. In the next round the target is 11. Players must throw 10 or less to win, again an easy task. Let’s say a few rounds later the target is down to 5. Now, more than half the dice throws will add up to more than 5 and therefore be invalid. It takes exponentially more dice throws to win, the lower the target gets. Eventually, when the target is 2 (the minimum possible), only one throw out of every 36, or 2% of them, will produce a winning result."

- Merkle root of the hash of that transaction that was added 60 minutes ago.

- The header hash of the transaction of the block that was added 50 minutes ago.

- The header hash of the transaction of the block that was added 40 minutes ago.

- The header hash of the transaction of the block that was added 30 minutes ago.

- The header hash of the transaction of the block that was added 20 minutes ago.

- The header hash of the transaction of the block that was added 10 minutes ago.

Why?

Because each hash is based on the hash of that transaction that was added an hour ago. Any modification of that hash alters each of the 5 blocks that comes after that. Each block of the 5 block’s data structure depends on that hash-value of that transaction you want to modify.

Step 10: Setting the Difficulty/Target to identify the nonce

Process: The difficulty is actually set by the peer-to-peer system itself reviewing that the average time for the last 2016 blocks was 10 minutes on average. If not, then the difficulty will be adjusted up or down to get to the 10 minute average.

Risk: Transactions will be mined in an untimely manner; i.e. more or less than 10 minutes.

Control: The difficulty/target effectively as a throttle to ensure that the blocks mined takes 10 minutes regardless the number the miners or the computers involved(i.e. which will continually fluctuate). What the target determines is the level of guessing that the miners have to do find the "nonce" (see next step). The lower the target the more difficult it is to guess that number because there are possibilities of the answer being correct.

Antonopoulos, in Mastering Bitcoin, gives the following analogy:

"To give a simple analogy, imagine a game where players throw a pair of dice repeatedly, trying to throw less than a specified target. In the first round, the target is 12. Unless you throw double-six, you win. In the next round the target is 11. Players must throw 10 or less to win, again an easy task. Let’s say a few rounds later the target is down to 5. Now, more than half the dice throws will add up to more than 5 and therefore be invalid. It takes exponentially more dice throws to win, the lower the target gets. Eventually, when the target is 2 (the minimum possible), only one throw out of every 36, or 2% of them, will produce a winning result."

Step 11: Produce the header hash, i.e. the proof of work

Process: The miners "brute force" (rapidly guess) what the right value of the nonce is to get the hash. The miners keep iterating the nonce, producing the hash, and checking if it matches the desired header hash. The series flows above is meant to illustrate the iterative process the miner goes through. If the miner guesses the right hash, they will be awarded the Block Award of 12.5 bitcoins. This reward halves every 4 years and there will only be 21 million bitcoins issued. The last bitcoin will be mined in 2140.

Risks:

Process: Timestamps are embedded in every calculation involved in generating the block. This makes the blockchain “immutable” as malicious actors can’t change previous blocks, especially after 6 blocks have been added to that block (i.e. which is why online retailers wait 60 minutes before accepting payment)

- Malicious actor controlling 51% of the network could authorize fraudulent transactions.

- People will not sign up to be miner without sufficient reward for their effort

- Infinite supply of bitcoins would expose the currency to inflation risks, i.e. if a bitcoins are mined endlessly the exiting bitcoins would decrease in value.

Controls:

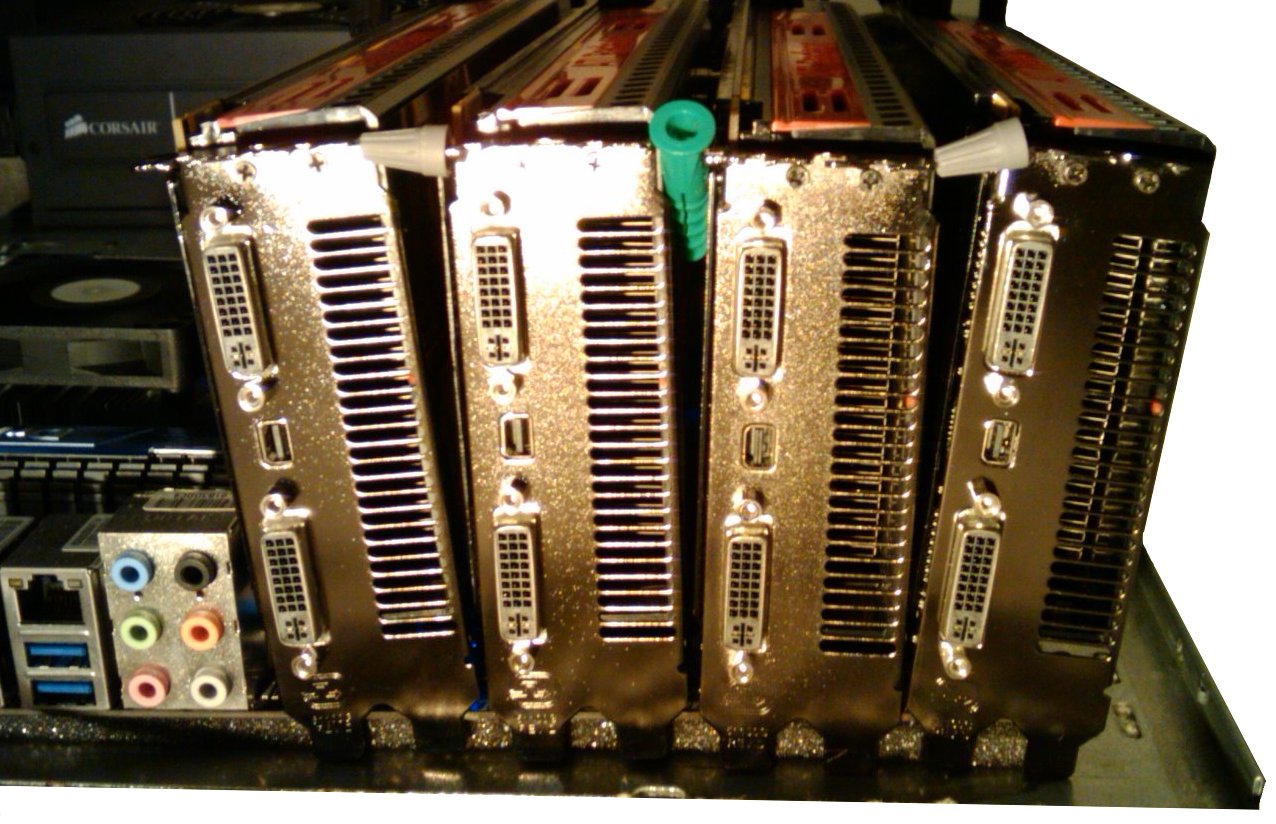

Mitigating Risk 1: As noted in the process above, the miners have to brute-force the nonce and therefore expend energy. In fact, "electricity makes up between 90 and 95 percent of bitcoin mining costs". That means miners have to invest capital, effort and energy to actually mine the bitcoin. As noted earlier, this investment ties the miner to the success of bitcoin. That is, they won't want to hack bitcoin as it would drive the value down. On the capital side, miners buy specialized equipment called "rigs" to mine bitcoin:

Mitigating Risks 2 & 3: The bitcoin reward provides the incentives to the miners to create the header hash that has the necessary elements. While the 21 million cap on bitcoins, actually makes the currency deflationary. As bitcoins get deleted or become inaccessible because some can't remember the password to their digital wallet - those bitcoins are gone forever. Consequently, the total amount of bitcoin in circulation will be less than 21 million.

Step 12: The block is time stamped

Risk & Control: As noted in Step 9, the blockchain concept of linking one blockchain to another is a sequence is one of the key controls to ensure that transactions will be modified in an unauthorized manner. Such a control is dependent on the timestamp as noted in the process section.

Process: Other nodes check the hash by running it through the SHA-256 hash function and confirm that the miner has properly checked the transaction. If more the 51% agree, then it is accepted as valid and added to shared blockchain ledger and it will become part of the immutable record.

Author: Malik Datardina, CPA, CA, CISA. Malik works at Auvenir as a GRC Strategist that is working to transform the engagement experience for accounting firms and their clients. The opinions expressed here do not necessarily represent UWCISA, UW, Auvenir (or its affiliates), CPA Canada or anyone else.

Step 13: Block is propagated across the network.

Risk: If miners added the block to themselves, they would have both access to gaining the asset (i.e. the bitcoin) and access to the ledger itself.

Control: The bitcoin network effectively segregates incompatible functions by requiring 51% of the network to agree that the work performed was valid. That is, a block cannot become part of the blockchain ledger until the majority of the network reviews the work performed by the miners.

Conclusion:

Hopefully, this has clarified some of the nagging questions you've had about how the bitcoin blockchain enables trust through a decentralized peer-to-peer network. That being said, the above flowchart has been quite the labour of love for the past few months. So there will be quite a few gaps! Special thanks to Andreas Antonopoulos, who although I have never met, has made this journey a lot easier by making his work available online.

Please email me at malik [at] auvenir.com if you have any comments, questions, or notice any gaps.

Hopefully, this has clarified some of the nagging questions you've had about how the bitcoin blockchain enables trust through a decentralized peer-to-peer network. That being said, the above flowchart has been quite the labour of love for the past few months. So there will be quite a few gaps! Special thanks to Andreas Antonopoulos, who although I have never met, has made this journey a lot easier by making his work available online.

Please email me at malik [at] auvenir.com if you have any comments, questions, or notice any gaps.

Author: Malik Datardina, CPA, CA, CISA. Malik works at Auvenir as a GRC Strategist that is working to transform the engagement experience for accounting firms and their clients. The opinions expressed here do not necessarily represent UWCISA, UW, Auvenir (or its affiliates), CPA Canada or anyone else.

Wednesday, May 17, 2017

Will auditors go the way of horses?

In late 2015, MIT Professors Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew Mcafee penned an article entitled, will "Humans go the way of horse labour?"

The article explores how the mechanization of farm labour serves as a model of exploring the automation of knowledge work citing the work of Nobel Prize-winning economist Wassily Leontief. They state:

How can this be applied to financial audit?

Firstly, the scope of the audit is driven by optimizing the cost-benefit curve. Consequently, there is a potential to get greater assurance for the same amount of resources allocated. Keep in mind that if auditors had to audit all transactions, the organization could go bankrupt just trying pay the audit bill. Consequently, auditors only look at transaction on a test basis.

However, with the increased datafication of an organization's interactions with stakeholders, there is an opportunity - that didn't previously exist - to analyze these interactions for audit insights.

Take for example a Business to Consumer (B2C) company, like Dell, that interacts with its customers via social media. In 2005, there was an infamous spat between a CUNY journalism professor, Jeff Jarvis, and Dell computers (original post here). Jarvis was irate over the customer service and has been an Apple customer since. Such conversations can be mined for potential audit implications. In this particular instance, it could be a means to assess the adequacy of the sales returns allowance - developing a model based on how many other customers have complained via blogs, twitter or other social media about the B2C company and then assessing whether the provision is adequate.

Previously, such an analysis would be cost prohibitive and wouldn't make sense for the auditor to even considering such a thing. For example, the B2C company would need to record all conversations and then have auditor listen to thousands of hours of conversations to see whether such an issue actually exists.

This is not to say that it is currently feasible to run such an analysis. Tools that aggregate, standardize and analyze such unstructured text could be argued to be in their infancy. However, datafication combined with further advances in social analytic tools (see video below for an example) in is the first step to a world where such analysis could be feasible.

The second separate but related issue is the role of the regulators in opening or closing the gate on innovation.

Some may mistakenly believe that this due to the regulated nature of audit. However, audit is not the only arena where innovation is shaped by the “regulator”. In fact, the success or failure of innovation depends on how the incumbents who govern the landscape make way for the new technology (or not).

Take for example the rise of the iPhone in the corporate environment. What allowed consumerization to take place (i.e. allowing users to connect their favourite smartphone devices to the network instead of the corporate devices) was that Microsoft took an open approach to licensing it Exchange Active Sync. They could have created a walled garden that allowed Windows Phone only to connect to their email server, however, they paved the way for iPhone and Android to connect their devices to the corporate email server. Microsoft as the "regulator" of which mobile device can connect to its mail server enabled the iPhone and Android to displace our beloved BlackBerries from the corporate environment. Had Microsoft saw more profit in walling off the market for its own devices the ability for Apple iDevice to disrupt corporate IT would have been stifled if not suffocated.

The article explores how the mechanization of farm labour serves as a model of exploring the automation of knowledge work citing the work of Nobel Prize-winning economist Wassily Leontief. They state:

"In 1983, the Nobel Prize-winning economist Wassily Leontief brought the debate into sharp relief through a clever comparison of humans and horses. For many decades, horse labor appeared impervious to technological change. Even as the telegraph supplanted the Pony Express and railroads replaced the stagecoach and the Conestoga wagon, the U.S. equine population grew seemingly without end, increasing sixfold between 1840 and 1900 to more than 21 million horses and mules. The animals were vital not only on farms but also in the country’s rapidly growing urban centers.

But then, with the introduction and spread of the internal combustion engine, the trend rapidly reversed. As engines found their way into automobiles in the city and tractors in the countryside, horses became largely irrelevant. By 1960, the U.S. counted just 3 million horses, a decline of nearly 88 percent in just over half a century. If there had been a debate in the early 1900s about the fate of the horse in the face of new industrial technologies, someone might have formulated a “lump of equine labor fallacy,” based on the animal’s resilience up till then. But the fallacy itself would soon be proved false: Once the right technology came along, most horses were doomed as labor."

But then, with the introduction and spread of the internal combustion engine, the trend rapidly reversed. As engines found their way into automobiles in the city and tractors in the countryside, horses became largely irrelevant. By 1960, the U.S. counted just 3 million horses, a decline of nearly 88 percent in just over half a century. If there had been a debate in the early 1900s about the fate of the horse in the face of new industrial technologies, someone might have formulated a “lump of equine labor fallacy,” based on the animal’s resilience up till then. But the fallacy itself would soon be proved false: Once the right technology came along, most horses were doomed as labor."

The MIT Professors are not alone in sounding the alarm when it comes to how automation can impact labour. Others includes Thomas Piketty, Douglas Rushkoff, Martin Ford and Nick Carr.

If the techno-distopians are right, then there will need to be a fundamental alteration of the way the economic system is structured to address the unemployed masses. Such masses are not likely going to take such things lying down. For example, in response to the Great Depression there were mass demonstrations in Washington DC where thousands protested their plight. In January 1932, Cox's Army of 25,000 assembled in the capital to protest their poverty. Later that year, the Bonus Army of 43,000 marched on Washington in the summer to demand the US government pay the bonus promised early: